Planning for the Future of Industrial Manufacturing

Speakers Share Their Expectations for the Next Seven to 15 Years

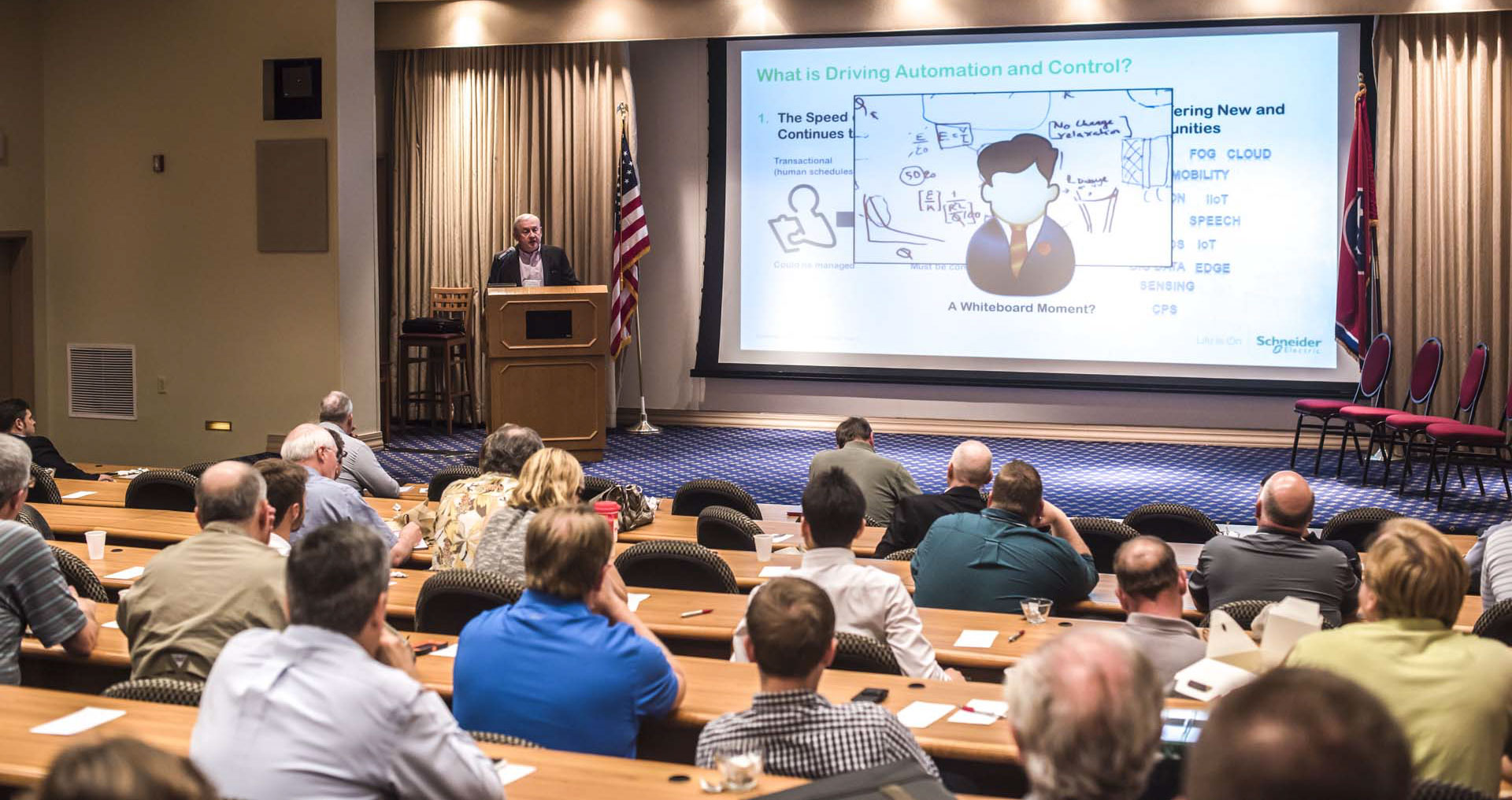

The control industry changed profoundly with the introduction of digital computers about 40 years ago, according to Dr. Peter Martin, Schneider Electric’s vice president of business value consulting. Control engineers, who had previously focused on solving control-related problems, suddenly became automation engineers who concentrated on the bits and bytes of computing, Martin said.

“We’ve been so focused on the technology that we forgot the technology was there to do something,” Dr. Martin said during a featured panel discussion at eChem Expo. That unfortunate shift in priorities was occurring just as Dr. Martin was beginning his engineering career, he told his audience in the packed meeting room.

“Every time some new technological whizzbang came out, you’d throw it into the control system … and it didn’t necessarily do anything,” Dr. Martin maintained during a discussion on the future of industrial manufacturing. As an example, he cited what he views as the fad of “expert systems” that prevailed in the 1980s. Calling anything an “expert system” guaranteed it would sell, he said.

Now, two factors are changing all that, Dr. Martin told the crowd. First, the speed of industrial business continues to increase as accounting switches to real time from previous constraints like monthly reports, he said. That means, for example, that the price of electricity can change every 15 minutes instead of remaining stable for relatively long periods, he noted.

Second, technology is now offering opportunities that never before existed, Dr. Martin said. On their own, none of the trends could reshape industry, but together they become formidable, he maintained. They include robotics, industry 4.0, mobility, virtualization, the Internet of Things, 3D printing and big data.

What’s happening, Dr. Martin proposed, is that the constraints imposed by technology – like communication, power and memory size – are falling. It’s akin to erasing the white board because the future no longer depends upon changing what now exists. Instead, engineers can imagine a perfect situation and work toward it, he said.

Controlling each asset in a plant autonomously – down to the level of pumps – would create a control system that perfectly fits the plant, Dr. Martin said. That would also result in simpler unit-level control strategies because all of the equipment is already under control, he noted. “The dream of unit control’s not fiction – it’s reality,” Dr. Martin said. From there, attention can move to area control and then to site-level and enterprise-level control, he said.

Control functions begin with consideration of constraints, Dr. Martin said. Specifically, security risk should be treated as a control problem and a cost of doing business, and provisions should be built into each asset to address environmental risk and safety risk, he urged.

Then it’s time to move on to the objectives, which include reliability, efficiency and operational profitability, Dr. Martin said. It’s difficult to understand the profitability of a pump, he admitted, adding that it’s not so difficult at the unit or area level.

The three real-time elements of profitability are the value of the product being produced, compared with the cost of energy and the cost of materials, Dr. Martin said. He encouraged his audience to strive for just-in-time efficiency. Labor costs aren’t included ing because they shouldn’t be changing quickly enough to warrant real-time monitoring, he said.

“As soon as management sees that safety has a direct role in the profitability of the plant, safety will become a mainstream business process,” Dr. Martin predicted. “It will be reported to the CEO.”

A real-time profit control loop that Dr. Martin presented illustrated the importance of measuring and improving processes to empower business. “Where does the data come from?” he asked. “Use sensors as your primary database, bring in business information as you need it –and you can do real-time accounting right down to the unit level.”

That information empowers everyone in the organization to see the effects of everything they do in the plant, Dr. Martin said. Thus, they learn how well their action are working out, he noted. “You can determine what every improvement you make adds to the bottom line of your company,” he said.

A Place for Drones

Another panelist, Aaron Cook, president of Aetos Group, noted that he’s a pilot who uses drones to monitor chemical plants. “What we do all day is play with robots in your facilities,” he told attendees.

But it’s more than merely playing. As someone who’s helping to shape the future of maintaining plants, Cook shared his thoughts on what’s to come. He began by using an example from the recent past to note the slipperiness of making predictions.

The iPhone, which many now view as a standard fixture of life, came into being in 2007, Cook said. And how has the smartphone helped change things? In 2008, it took all year to generate 210 billion email messages. Some 205 billion were sent in just a single day last year, he said.

Despite that example of unpredictability, Cook was willing to predict that plants will soon have control towers to operate more than one drone at a time as they make surveillance runs throughout a plant. In flight, the drones will coordinate with with earth-bound inspection robots and submersible observation equipment, he said.

The drones in the air, on the ground and beneath the surface of liquids will pick up signals from sensors scattered throughout the plant, Cook noted. The sensors will be built into the equipment and have five-year battery life and signals that drones can pick up from 10 feet away, he said. Airborne drones will dwell in rooftop bubbles, while employees will stow submersibles in boat houses.

Such changes won’t occur over night and won’t come without effort. “It’s steps,” Cook said. “You’re going to have to be OK with some failure.” But companies can work together to absorb the financial cost of failure and create an environment that fosters innovation, he predicted.

Eliminating the Unplanned

Speaker Tim Holtan, said that as senior project manager in asset performance management for GE Digital, he helps manufacturers avoid unplanned downtime, increase intervals between major outages and, hopefully, eliminate failure.

To accomplish all that, GE is introducing its customers to Predix, a platform it has used in-house to reduce manufacturing expenses by half a billion dollars a year, Holtan said. “It’s specifically designed for industrial applications and the industrial internet,” he said of the platform. “It’s now available to everyone.”

Over the next seven to 15 years, GE expects to see widespread adoption of the platform, Holtan noted. He recommended that companies explore ways of using Predix by employing the principal of industrial microservices. That means starting small with one or a few apps, a small number of people, a short period of time and a limited budget to find out what innovations work and who will use them. “Do the minimum to develop your capabilities,” he advised.

Companies can also create a culture of DevOps to create new features continuously, a practice that Facebook and Google use, Holtan said.

Customers can also benefit from the industrial platform as a service that GE is offering with Predix, Holtan maintained. He compared that benefit to the way GE itself has built the platform by capitalizing on approaches to big data and reductions in storage costs that many companies have helped develop.

The near future will also bring wider use of the digital twin that provides a picture of what equipment should be doing, compared with what it’s actually doing, Holtan continued. That can help fulfil the dream of eliminating spare equipment in process plants, he said. It’s a dream he has had since visiting plants in Japan where companies chose to use a single good pump instead of two mediocre ones.

Digital twins can also do away with the need for personnel on offshore drilling platforms because the rigs are controlled remotely, he said, noting that one oil company has built a nearly exact replica in Houston of a drilling platform in the Gulf of Mexico. “Tt’s going to be a quantum leap,” he said of the reduction he foresees in the number of people working offshore.

Open automation, another idea on the horizon, could promote innovation, integrate the best components, provide access to leading-edge capability, preserve the asset owner’s application software, lower the cost of future replacement, and employ an adaptive intrinsic security model, Holtan said.

In conclusion, Holtan expressed hope that industry could use advances in technology to help achieve something he deems vital. “Maybe you can help me declare war on spare equipment,” he urged the audience. “That’s a war we can win.”

Re-creating the Workforce

With skilled, knowledgeable, experienced workers retiring in great numbers, it’s imperative to train their replacements, according to another speaker, Jeff Frazier, dean of the Regional Center for Advanced Manufacturing at Northeast State Community College and an experienced Eastman Chemical Co. employee.

Imagine an employee, Frazier suggested, who’s been with the company 20 years, has more experience that any of his or her coworkers in certain areas, solved specific problems that arose, led key projects and has a deeper knowledge than anyone else in the plant on some subjects. “These people are walking out the door in droves now,” he warned. “They understand control in a context that people might not have today.”

Replacing them is complicated by the daily introduction of new technology, a nationwide shortage of skilled labor, a lack of soft skills like communication and teamwork, and a culture in schools that doesn’t inform young people of opportunities in manufacturing, Frazier said.

Preparing plants for the future will require companies to sharpen their focus on knowledge retention and transfer, broaden participation in workforce development, participate in regional workforce opportunities, and offer more internships, Frazier maintained. “So our companies are going to be called on to take some roles different from what we’re used to,” he said.

But embracing the unfamiliar can pay off, Frazier predicted, because companies can gain a competitive advantage by developing a better workforce. That task can begin as far “upstream” as middle schools and elementary schools, he noted.

[apss_share]